For almost everyone currently not in hibernation, COVID-19 is without a doubt the most discussed and apparently controversial topic on the go. From social media to the political discussions of Westminster, everyone is having their say. Regardless of position, what it is, is prime opportunity to witness science in action. I’d like to spend some time picking apart the idea that herd immunity is the best strategy moving ahead.

Now that we are a number of months into dealing with the pandemic, its clear to see that a number of distinct schools of thought have developed with respect to how we should go forward with COVID-19. Most notable in my opinion is the dichotomous structure of public health versus the economy. I could write about all of the possible arguments for and against the different positions on each side of the fence across multiple posts but I want to take some time to address what appears to be, the most common of the arguments. It’s actually an old argument dressed up to suit the current state of affairs and it’s commonly stated in a manner similar to the following;

“We need to learn to live with COVID-19. What we should be doing is shielding the elderly and vulnerable and anyone who isn’t comfortable going out, and the rest of us just need to get on with it!”

This statement is a guise of the herd immunity strategy and it is easy to see why it is so appealing to so many. For a start, there isn’t always a clear answer or one that can guarantee a short term answer. This idea ticks both those boxes. Why not protect the people who need protected and let everyone else carry on as they please? Secondly, it’s something we can act on immediately. Begin putting good strategies in place for those shielding. We already have schemes in place that were used for the general population and if we can repurpose those then we are onto a winner! Everyone else gets back to work, the economy can start to recover, and we get onto the endgame strategy as soon as possible.

It all sounds wonderful, but unfortunately the idea of a herd immunity strategy rests on a number of flawed premises.

- Herd immunity has never been observed to occur naturally.

- There needs to be a lasting immunity to the pathogen.

- A high percentage of the population needs to achieve that immunity.

So lets tackle these premises one at a time. Firstly, herd immunity is something that has only ever been described in the context of diseases where a vaccine is available to the population. In no uncertain terms it a vaccine that allows us to even achieve herd immunity in the first case. A fairly obvious problem for this premise then, is that at the time of writing this we don’t have a vaccine in circulation. Not only that but at this stage even when we have a number of vaccine candidates in phase III clinical trials, it is too soon to be planning as if we do have one available. It would be careless and illogical to chase an achievement knowing it is in fact unattainable. An interesting article published in The Lancet is a fantastic outline of how herd immunity came to be, when it was first described, and how it applies to COVID-19.

Lasting immunity to the SARS-CoV-2 virus is not something we have enough data on to be making decision about whether or not we should be chasing a strategy that relies on it. In fact a number of more recent studies have come to light showing that there is a peak of immunity but it wains over time. Moreover, there are a number of cases of reinfection coming to light which certainly doesn’t stack the evidence in favour of a lasting immunity. Essentially, where immunity to pathogens goes through peaks and troughs, you’re left with an exponentially more difficult time, achieving herd immunity. Instead of a simple case where you give an individual immunity and then move on to the next, you’re left with a scenario whereby you need to provide that immunity timed conveniently enough that the required percentage of the population are all immune at the same time. Where individual immunity drops out, the total percentage of immune persons also drops. As the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health puts it;

“For infections without a vaccine, even if many adults have developed immunity because of prior infection, the disease can still circulate among children and can still infect those with weakened immune systems. This was seen for many diseases before vaccines were developed.”

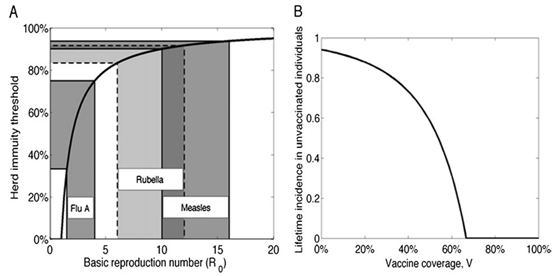

This leads nicely onto the final premise. The level of the population needing to be immune to reach what we consider to be herd immunity, is always extremely high. In nearly all recorded cases of successful herd immunity the percentage of the population immunity is extremely high. Most studies measure this by vaccine uptake and as can be seen in the below graphic, the relationship between incidence of disease and coverage of the vaccines available for said diseases shows how important vaccination protocols are for those who cannot receive them. Part B of the graph is modelled on the non-vaccinated population i.e. the percentage of vaccine coverage listed along the X axis, reflects the benefit to the unvaccinated population in terms of the incidence of the disease amongst that population, listed on the Y axis.

Having such a high percentage of the population of the population immune comes with its own challenges. For a start, I would like to outline a simple exercise in percentages. Lets say I have 100 people in my scenario. If I assign an arbitrary value of 80% as the level at which herd immunity is achieved, then I need 80 people to be vaccinated so that the entire sum of people are protected. So if I take 20 people and I hide them out of the way and simply ignore them, what percentage of my population is now immune? Under the premises outlined by the pro herd immunity crowd, the answer would be 100%. There are 80 people left and all of them are immune so we have achieved 100% immunity. This however is not the case. If these people are still members of that population, they are still counted. So I still only have 80% of my population immune. In this scenario, this is enough to maintain immunity, but would it realistically be enough for a worldwide population? What percentage of our population would require shielding or would be unable to get a vaccine if it became available? How do we then go about making the decision to shield these individuals when we don’t even get past the first hurdle of knowing at what population percentage we could achieve herd immunity? The fact of the matter is this. Shielding doesn’t remove those people from your population total. The only way to do that, is to make them non-existent as a contributor to that total. Whilst those people are shielding but still members of the total population they in fact bring down the total percentage of immune individual’s making it more difficult to reach the required levels of immunity. Another crutch for herd immunity which can’t hold up to scrutiny.

As we can see from the above, herd immunity is not a viable strategy from where we currently stand. Not only do the listed premises not stand, but there are many more which I didn’t consider significant enough to make the final cut. I could have discussed the financial implications of rolling out a vaccine worldwide. Something that would certainly be of detriment to the economy in the early stages. Does the short term economy trump the long term economy and would these initial financial losses be acceptable to those who are so strongly pro-herd immunity? What about the logistical issues associated with the necessary distribution of a worldwide vaccine? What would happen if the anti-vaccine community was somehow successful in encouraging enough people to avoid a vaccine? My idea for this article isn’t to address each and every possible flaw or argument of statement, but to address the main ones. The ones that I see most often, that are repeated the most, the ones with the most drastic pull on those around us.

Naturally, from my perspective I place a higher emphasis on Public Health than I do the economy. This is not to say I don’t understand the importance of the economical perspective, quite the opposite. I don’t even claim to have to have the singular and infinitely correct way of thinking. However, it’s important that we don’t mistake short term, simplistic answers, for the correct answers. It makes no sense to rest on our laurels in the wake of a demonstrably flawed argument. As with all science, this is not something we can dismiss. As answers come up to some of the questions raised above it will be important to again ask the main question pushing this narrative. Is herd immunity now a valid strategy? As I have alluded to, the answer is no for now. Future developments may shift the answer but until such times we cannot make plans off the back of arguments and statements which can be easily proven wrong. I am not in the habit of backing strategies with such low odds of success.