Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is one of the most well researched and understood genetic blood disorders. Despite this, its impact is profound both clinically and socially. At its core lies a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), just one nucleotide change is all that’s required for such significant downstream effects ranging from red cell morphological changes to global health schemes. This post takes a walk through that journey from the SNP through to the sickling and how such a small change can lead to such a big problem.

The Genetic Switch: The SNP

The mutation responsible for sickle cell disease is famously very simple and easy to remember if you’re studying. It’s a single nucleotide polymorphism in the beta globin gene on chromosome 11. In this case, adenine is replaced by thymine at codon 6. This GAG – GTG switch causes a shift in the amino acid chain from glutamic acid to valine. This seemingly very small shift in only a single nucleotide produces some dramatic implications and ultimately leads to the production of a different form of haemoglobin being produced. In normal aduts the predominant haemoglobin in production is HbA which is composed of two alpha and two beta globin genes. Patients with sickle cell disease instead produce HbS which behaves very differently to HbA under certain conditions.

Protein Level Consequences

Glutamic acid is hydrophilic, whilst Valine is hydrophobic. In the HbS where the valine is present, this makes the resulting molecules essentially stickier. They have a greater tendency to stick together in low oxygen conditions. Whilst HbA remains dissolved intracellularly irrespective of oxygen tension, HbS tends to polymerise when it is deoxygenated. Of course the purpose of a red cell is oxygen delivery so the capacity of a red cell to become oxygenated and deoxygenated in repeated cycles as oxygen delivery occurs, is key to cell function and longevity.

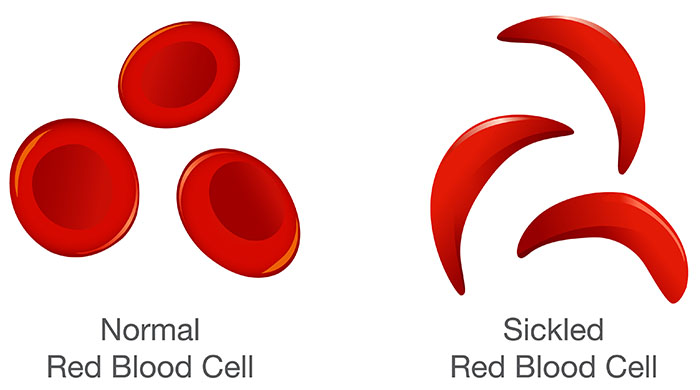

This polymerisation forces a change is the physical shape of the red cell and we see a shift from a flexible, biconcave disc to a very rigid and distorted sickle shape.

Figure 1. A visual comparison of normal RBCs and sickled RBCs.

The Issue with Sickling

Ok so the red cells are a different shape so what? Well there are two main issues.

- They’re inflexible.

- They’re lifespan is significantly reduced.

These issues lead to vaso-occlusion where sickled red cells block smaller blood vessels, causing severe pain in patients alongside tissue damage and organ dysfunction from infarction. The premature breakdown of the cells in circulation leads to a chronic anaemia and consistently low haemoglobin. Finally, the splenic dysfunction that occurs from all of this increases risk of infections, especially in children.

Global Impact

Sickle cell disease is particularly common in populations where malaria is or was historically prevalent. This is because of a very interesting evolutionary development that is known as heterozygote advantage. Individuals who have a single copy of the sickle cell gene (HbAS) are less likely to suffer from malaria due to a number of factors associated with heterozygous inheritance.

- Impaired parasite growth – where an RBC is infected, HbAS cells are more likely to sickle under low oxygen situations and thus the cell is less hospitable for parasites.

- Enahnced immune clearance – HbAS cells are targeted and removed more efficiently by macrophages, limited replication potential.

- Limitations of infection – HbAS cells can still become infected but are much less likely to go on to develop severe anaemia or respiratory distress because of the reasons above. This increases survivability for individuals.

Diagnosing Sickle Cell

A number of techniques are used currently to diagnose or assist in the diagnosis of SCD. An FBC and associated film are the first port of call. These will often show a microcytic anemia and reticulocytosis with the film further revealing sickle cells themselves, target cells, and Howell-Jolly bodies.

Sickle solubility test is the next test. This is often done at a district general hospital and allows for a screening of the presence of HbS by relying on the fact that HbS in a reduced state is less soluble in concentrated phosphate buffers than nearly all other haemoglobins. I say nearly all because this is science after all, so there are always exceptions but in this case they are rare. The sickle solubility test is importantly not diagnostic alone and any positive tests (even negative ones in some circumstances) should be followed up with our next test.

Haemoglobin electrophoresis. This is our primary diagnostic test for SCD and can be used to identify and quantify different types of haemoglobin present in the blood. The technique separates haemoglobin variants based on their electrical charge and mobility when exposed to an electric field. In SCD, electrophoresis typically reveals the presence of HbS, and may also show HbF (fetal haemoglobin) or HbA2, depending on the genotype. Unlike the sickle solubility test, haemoglobin electrophoresis provides a definitive diagnosis, distinguishing between sickle cell trait (HbAS), sickle cell disease (HbSS), and other compound heterozygous conditions such as HbSC or HbS/β-thalassaemia.

Sickle Cell Management

At the time of writing this article, there is no cure for SCD, and management of the disorder is focussed on managing symptoms and preventing complications. Whilst this can lead to a varied approach that is very patient specific, there are some common treatment plans used across patients;

- Pain management can be done with over the counter medications such as paracetamol or ibuprofen, although patients in sickle crisis or those hospitalised may need stronger prescription pain relief from opioids

- Hydroxyurea: Increases fetal haemoglobin (HbF), which interferes with HbS polymerisation.

- Folic acid: Supports red cell turnover. Pain management: Critical during vaso-occlusive crises.

- Vaccinations and antibiotics: To prevent infection in asplenic or hyposplenic patients.

- Regular monitoring: Including transcranial Doppler in children to assess stroke risk.

Emerging Therapies and Research Advancements

While hydroxyurea and management of symptoms remain the main effort of sickle cell disease (SCD) management, research is advancing rapidly with new therapies offering hope for the future.

1. Gene Therapy and Gene Editing

One of the more exciting developments is gene therapy which aims to correct or bypass the HbS mutation in a patient’s own cells.

Exa-cel (exa-cel / CTX001): A CRISPRCas9 is a gene editing therapy that reactivates production of fetal haemoglobin (HbF) by disabling the BCL11A gene which naturally suppresses production of HbF. Increasing HbF prevents sickling, as HbF does not polymerise like HbS.

LentiGlobin (Bluebird Bio): A lentiviral vector introduces a functional β-globin gene into a patient’s stem cells to restore normal haemoglobin production.

Both approaches require myeloablative conditioning (i.e. chemotherapy to prepare the bone marrow) and are currently very expensice as all new therapies tend to be but show promising cure rates in early phase trials and compassionate use cases.

2. Novel Drug Therapies

Voxelotor is a new drug designed to Increase haemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen, which prevents HbS polymerisation. Shown to reduce haemolysis and improve haemoglobin levels.

Crizanlizumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks P-selectin, reducing red cell and leukocyte adhesion in the endothelium in an attempt to reduce vaso-occlusive crises.

L-glutamine which is approved in the US is supposed to reduce oxidative stress in red cells, thought to help prevent sickling.

These drugs don’t cure the disease, but can reduce complications, improve quality of life, and offer alternatives for patients who are not candidates for transplant or gene therapy.

3. Bone Marrow and Stem Cell Transplantation

Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains the only widely used curative therapy for SCD. It replaces the patient’s defective marrow with donor cells capable of producing normal haemoglobin. However, this option is limited by donor availability, risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and the need for intensive conditioning regimens.

Final Thoughts

Sickle cell disease is a powerful example of how a single mutation can alter the shape, function, and fate of red blood cells. From the genetic code to a complete clinical crisis, the journey of sickle cell disease is shaped by science but its impact is felt across the world every day. As research pushes the boundaries of what’s possible, from gene editing to novel biologics, the future for patients with SCD is brighter than ever. But even now, understanding the disease from “SNP to sickling” empowers us as scientists, clinicians, and advocates to deliver care that’s informed, compassionate, and future facing.