Immature Granulocyte (IG) flags are more than just a numerical threshold they’re an insight into a patient’s underlying immune response. Whether you’re new to blood film review or an experienced BMS refreshing your practice, this guide will walk you through how to approach samples flagged for IG review, how to decide if a manual differential white cell count (DWCC) is needed, and how to interpret what you see on the slide.

Why Do IG Flags Matter?

Immature granulocytes in the peripheral blood can often indicate an early stage response to infection, inflammation or stimulus that may be affecting the bone marrow. Pregnant women and neonates may have raised IG% by the nature of their physiological adaptations at the time of presentation, however some patient groups will benefit significantly from effective IG% assessment. This includes patients who are highly susceptible to infection where an increasing IG% can help determine the severity of an early innate immune response. Particular attention should be paid to;

- Patients with HIV/AIDS

- ICU Patients

- Patients on Chemotherapy

Most importantly, the stimuli affecting the bone marrow can include malignant neoplasms of the blood and bone marrow and as such it is important to be able to review films where the IG% is >5.0 and make an assessment of whether or not a manual count should be performed.

Understanding the Sysmex IG Flag

The Sysmex XN series analyser provides leucocyte differential analysis which includes the detection and quantification of immature granulocytes. These immature granulocytes are not included in the standard 5-part differential that is attached to the full blood count (FBC). Many laboratories will assign a numerical threshold value above which these IG flags should be reviewed. In my case this lies at >5.0%. Any samples which breach this threshold must be manually assessed to determine the accuracy of the count and determine whether a manual DWCC should be performed. This process ensures diagnostic accuracy and appropriate reporting of samples to the responsible clinician.

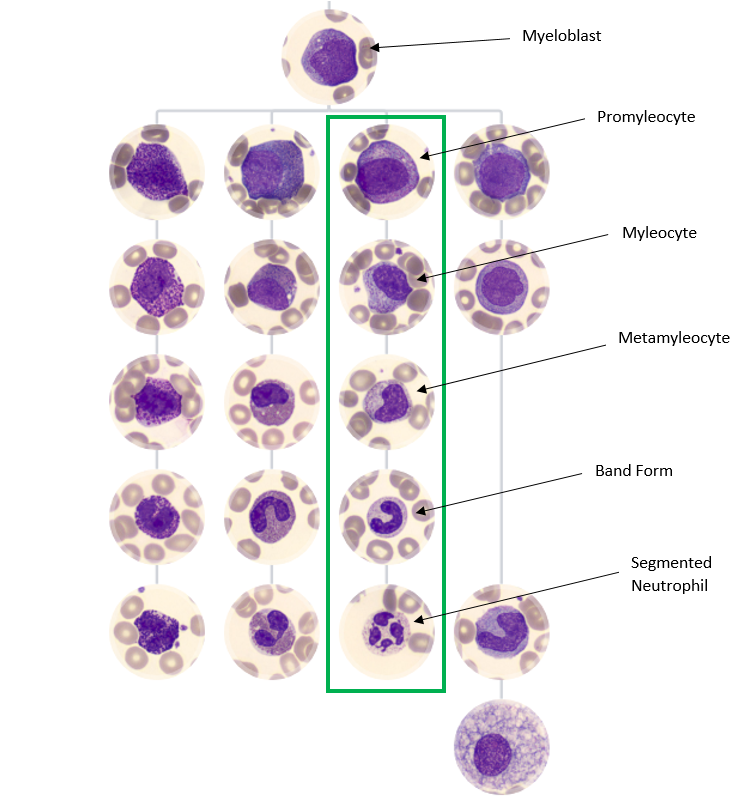

The immature granulocytes which are counted in the analyser and contribute to the generation of an IG flag include metamyelocytes, myelocytes, and promyelocytes. These cell types are not normally present in peripheral circulation under normal circumstances and their presence can be a sign of infection, inflammation, bone marrow stimulation, or haematological malignancy. The process of normal myelopoiesis is highlighted below, showing the pathway of differentiation beginning with a myeloblast at the top and working down towards fully matured cells at the bottom. The neutrophil lineage is highlighted for reference. The first step of development from a myeloblast is the promyelocyte. This is the first committed step of neutrophil differentiation which continues down the image to a myelocyte, metamyelocyte, band form, and a segmented neutrophil.

Myelopoiesis

In the healthy patient, myelopoiesis occurs primarily in the bone marrow, as far as the band form stage of differentiation. Once fully matured, the cells extravasate from the bone marrow and enter peripheral circulation. Numerous factors can stimulate the bone marrow to release myeloid precursors into the peripheral circulation. This can include compensation for an increased turnover of cells due to infection or inflammatory processes, genetic aberrations which result in uncontrolled cellular proliferation, or drug induced bone marrow production.

Figure 1. Adapted from https://www.cellwiki.net/en/cells (2025)

Morphology: Recognising Immature Granulocytes

Promyelocytes

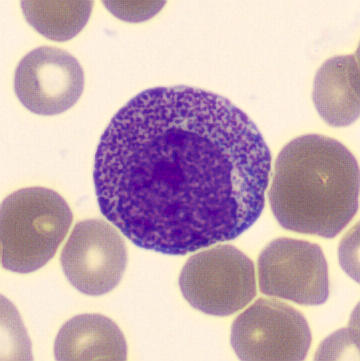

Figure 2. A Promyelocyte seen in the peripheral blood surrounded by erythrocytes.

Promyelocytes are generally larger than myeloblasts with their nuclei being similar in sizes. The cytoplasm of the promyelocyte is more abundant at this stage. The nucleoli are often present but will begin to close and become less prominent than in the blast stage. The chromatin of promyelocytes tends to become slightly more coarse and clumped than the chromatin pattern present in a myeloblast.

Promyelocytes gritty basophilic color to their cytoplasm and it will contain prominent primary granules. These granules will look like red/purple grains of sand. Careful examination (enhanced by oil immersion) shows these granules to be cuboid shaped as opposed to round.

- Nucleus: Large round or oval, eccentric nucleus with fine chromatin pattern. May contain up to 3 nucleoli.

- Cytoplasm: Basophilic colour with the presence of primary azurophilic granules. Granulation lays in both the cytoplasm and over the nucleus. Golgi zone is present.

- Other Features: No secondary granules present, much larger than other cells in the lineage.

*Special note* If large numbers of promyelocytes are seen or the promyelocytes identified appear abnormal, you should consider the chance of APML. If unsure, please immediately seek the guidance of a fully DWCC trained member of staff for assistance.

Myelocytes:

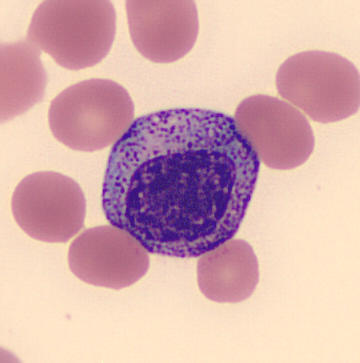

Figure 3. A Myelocyte seen in the peripheral blood surrounded by erythrocytes.

The next stage of maturity in the myeloid lineage is the myelocyte. The cytoplasm at this stage begins to produce specific, secondary granules. If the cell is destined to be a neutrophil these secondary granules will be pink or tan brown and will cause the basophilic colour of the primary granules in the promyelocyte to lighten and breakup. These secondary granules are most obvious in the golgi zone directly adjacent to the nucleus. An area that appears unstained due to the presence of the golgi apparatus. As the cell matures closer to a metamyelocyte these secondary granules fill the entire cytoplasm.

While the cytoplasm shifts to producing secondary granules it also loses the prominence of its primary granules. In situations where the bone marrow is stressed or forced to make neutrophils quickly, as in sepsis or during certain therapeutic injections, some of these primary granules may persist and this is referred to as toxic granulation.

Concurrently with the production of secondary granules the nucleus begins to shrink and condense. The nucleoli close and disappear, the chromatin becomes more dense and clumped, and also becomes tighter darker and more compact.

- Nucleus: Round/Oval and often slightly eccentric. Fine chromatin pattern but clumping remains present.

- Cytoplasm: Light blue to lavender with abundant secondary granules. May have an apparent golgi zone, adjacent to the nucleus.

Other Features: No nucleoli, no nuclear indentation

Metamyelocytes

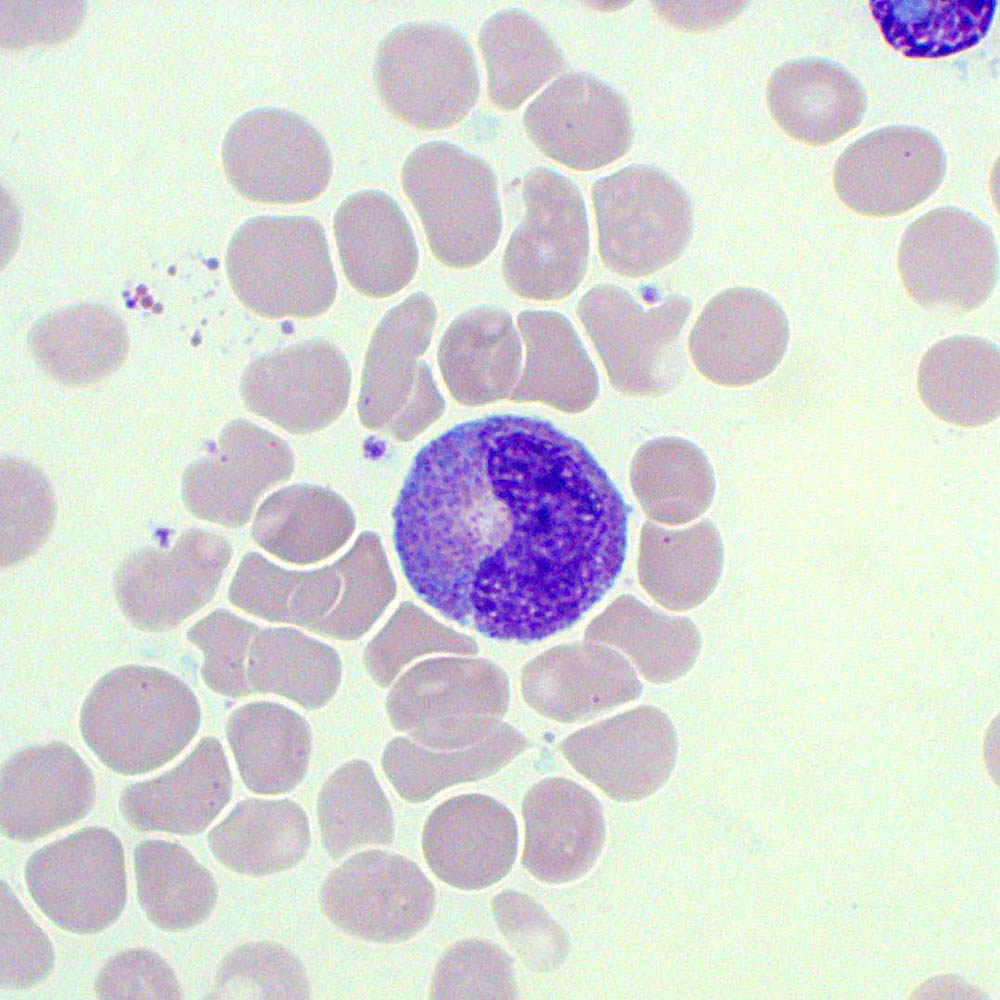

Figure 4. A metamyelocyte with a visible golgi zone. The cell is surrounded by erythrocytes and thrombocytes are also visible.

During the metamyelocyte stage the cytoplasm and nucleus continue to decrease in size. The cytoplasm achieves full secondary granule content. The chromatin at this stage appears to be more dense and compacted while the nucleus begins to indent and acquire the familiar “kidney bean” shape. By the end of this stage the cell will be similar in size to a mature neutrophil with similarly cytoplasmic granularity.

- Nucleus: Kidney shaped or indented but not fully segmented with moderately clumped chromatin.

- Cytoplasm: Abundant, pale pink to light blue with specific secondary granules present dependent upon differentiation pathway i.e. whether the metamyelocyte will develop into a neutrophil, eosinophil, or basophil.

Other features: No nucleoli, few or no azurophilic granules.

Summary Table

| Feature | Promyelocyte | Myelocyte | Metamyelocyte |

| Nucleoli | Yes | Faint/Absent | No |

| Nucleus | Round and eccentric | Round/Oval | Indented |

| Chromatin | Fine | Slightly clumped | Moderately clumped |

| Cytoplasm | Deep blue | Pale blue/lavender | Pale pink/blue |

| Granules | Primary | Secondary | Secondary |

Use the following questions to guide your review:

1. Are immature granulocytes present in multiple fields? → Yes = Perform DWCC

2. Are the IGs numerous or morphologically concerning? → Yes = Perform DWCC

3. Does the auto DWCC match what you’re seeing? → No = Perform DWCC

4. Would removing the IGs from the neutrophil count affect interpretation? → If yes, or you’re unsure, perform DWCC.

If you’re unsure about morphology or significance, escalate to a DWCC-trained colleague. Always document your decision.

Clinical Context Matters

Understanding the clinical background is critical to interpretation. Here are examples where IGs could significantly affect interpretation;

Febrile Neutropenia – IGs may mask neutropenia

Oncology Patients – Neutrophil trends affect treatment decisions

Sepsis – IGs part of early left shift response

Bone Marrow Suppression – May reflect regeneration or new pathology

Haematological Malignancy – Atypical IGs may guide diagnosis or monitoring

Infection/Inflammation – IGs can rise without WBC/neutrophil rise

Post-surgical or Trauma – Reactive IGs must be distinguished from pathological causes

Adjusted Neutrophil Count: A Subjective Judgment

Since IGs are counted in the standard neutrophil percentage, a high IG% can artificially inflate the neutrophil count. Ask yourself:

Would the neutrophil count still be clinically valid if I removed the IGs?

Example Scenarios:

– IG 8%, WBC 10.0, Neuts 6.0 → Adjusted ~5.2 → Probably fine

– IG 8%, WBC 3.0, Neuts 1.2 → Adjusted ~0.96 → Clinically significant

– IG 15%, WBC 12.0, Neuts 4.0 → Adjusted ~2.2 → Possibly significant depending on context

You don’t need to manually recalculate, but you do need to assess the clinical impact.

Summary: Your IG Flag Checklist

✅ IG% > 5.0

✅ Scan film at x20 → assess monolayer

✅ Switch to x40 → identify IGs

✅ Are they numerous? Across multiple fields?

✅ Is the auto DWCC consistent with what you see?

✅ Would IGs skew the neutrophil count?

✅ Escalate if unsure

✅ Document your decision

Final Thoughts

IG flag assessment sits at the intersection of automation and professional judgment. As biomedical scientists, our ability to interpret what the analyser flags — and to decide when to override it — directly affects patient care. Learning to spot the patterns and escalate when needed is a key part of our diagnostic role.

Leave a comment