For many years, the field of genetics has been undergoing a diverse change. The nomenclature in common use has continued to change and develop in new ways as the field grows more complex with ever more fascinating areas of study. The suffix “omics” has overtaken a large portion of what we scientists can now study and I plan to dedicate this article to genomics, giving you an understanding of what it is and why it is the next big thing for many who work on the level of the gene.

So the suffix “omics” then. What is it? That’s actually not quite as simple to answer as you think. The suffix itself is what we call a neologism. It’s a new term that’s entering common language that hasn’t been accepted for mainstream use. If you’ve been around in the scientific community for the past ten years or so, you’ll have seen this creeping around for a while, gradually becoming incorporated into the vocabulary of many of your colleagues. On a general note “ome” has been used in biology to refer to something in totality, so when we apply “omics” as a suffix what we are trying to say is that it is the study of the whole subject. The big one I will be discussing today is genomics. The study of the genome.

Now this may be a variation from what most of you may have referred to as genetics. Genetics was the study of genes but as time has gone on we have evaluated the much greater need for the study of the human genome. What we realise now is that with this area becoming more complex each and every day, that studying genes in isolation is not giving us progression at the rate which we want it. Instead, studying a gene with respect to the whole genome we can better understand its function and place.

What I would like to start with, is a quick recap on DNA and genetics…

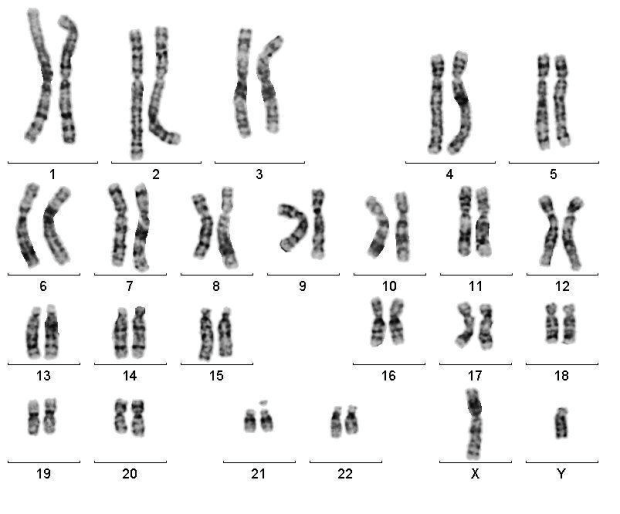

So your DNA is housed within the chromosomes in the nucleus of your cells. Each cell contains 23 pairs of chromosomes of which you receive one pair from your mother and one pair from your father.

As you can see in the above picture, there are 23 pairs. The last set of chromosomes are the sex determining chromosomes. X and Y. If the combination you possess is XX you will be a female and if you have a Y chromosome (XY) you will be a male. So in the above image showing the last pair as XY, this individual is a male.

As you can see in the above picture, there are 23 pairs. The last set of chromosomes are the sex determining chromosomes. X and Y. If the combination you possess is XX you will be a female and if you have a Y chromosome (XY) you will be a male. So in the above image showing the last pair as XY, this individual is a male.

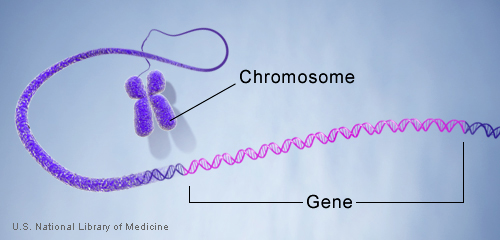

These chromosomes contain all of the genetic information your body needs and will ever need. It codes for the colour of your eyes and hair right through to regulating the life cycles of your cells and and determining when certain proteins need to be synthesised. So within these chromosomes when we look closer, we can see individual genes. Genes are the functional unit of heredity i.e. they are what we pass on to our offspring and what we inherit that give us certain characteristics. Genes tend to act as a set of instructions for synthesis of proteins however not all of them are coding genes. They vary drastically in size as well, some genes can be as little as a few hundred bases and some as large as 2 million bases.

(Credit: U.S. National Library of Medicine)

So wait, whats a base? In the picture above you can see an unwound length of chromosome and the pink highlighted gene. If you recognise this characteristic helix shape, you’ll know that it is DNA or deoxyribonucleic acid. Famously discovered in 1953 by James Watson and Francis Crick after a significant amount of help on the X-ray crystallography side of things, from their PhD student Rosalind Franklin. DNA is made up of four, chemical bases. Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C). The human genome consists of 3 billion of these bases and their order determines everything to do with genes and their functions. From when and where to express them, through to what protein to synthesise. It really is quite a spectacular series of events.

These bases pair up together in the same manner, always. There is never any variation at this stage. Adenine always double bonds to thymine, and cytosine always triple bonds to guanine. No exceptions (in DNA).

So now that we are here and you have acquired a good understanding of some of the basic genetics. I’m going to take the opportunity to break down an example of some bad journalism. This is something that really grinds my gears as a science communicator and as someone who is trying to make science accessible for the masses. I’m sure that you wont need convinced that journalists are all about their sensationalist headlines. When it comes to science they are on a whole other level. The information we tend to be trying to provide the public can be delicate and needs a certain understanding to be met. So when journalists rush in with major headlines to shock the world with, they tend to be wrong. Generalising science can be a dangerous game and here’s an example of why:

If you’ve been reading between the lines in some of the above information and piecing it together with bad journalism you may have some questions. If everyone has 3 billion bases, then how can some people have the bad genes? you know the cancer causing ones they talk about in the news? Or the numerous genes that give you this or that etc. like some of the headlines in the picture below for example…

Please allow me to alleviate your fears from the outset. You have the BRCA1 gene. WAIT WHAT?

This is a perfect example of bad journalism harming everyone. The profile of your genes is the same as mine and it is the same as everyone else. We all have the exact same (roughly 23,000) genes. What the issue actually was for Angelina Jolie and for many other individuals is a MUTATION in the BRCA1 gene. Certain mutations or base changes at various points in the BRCA1 gene can lead to increased susceptibility to acquire forms of breast cancer. But the gene itself is not one that you have and then you get breast cancer. So next time you read a headline asking if you have gene X and telling you that you may be at risk. Take it with a pinch of salt and go forth with your new knowledge.

So I’ve digressed a little but I think it was for good reason. But lets get back to the main topic. Genomics. So this new area of study, how has it come about, what is it doing exactly and why is it only now beginning to thrive?

It was in 1984 that scientists launched the human genome project. An ambitious yet necessary expedition in which these individuals sought to map out every single base in the human genome, all 3 billion bases that is. By doing so, they hoped we could begin to understand structures and functions better. Realise greater potential for clinical genetics and be able to map what all of our genes did and why they did it. It was in February of 2001 that this was completed and the full map was published in Nature. A prominent scientific journal.

With the full map, came some answers. But as with all science it wasn’t quite that simple and along came some more questions. Which I will now pose to you. So Homo Sapiens is the most evolved and complex organism walking the face of the earth today. We use numerous languages to communicate with each other, we form social groups and engage in problem solving, logic problems, mathematics, science and many obscure and abstract tasks. We can think, we can feel and we can do.

With this in mind lets look at the numbers. So we have 3 billion bases, and 23,000 genes. If we work out some rudimentary maths we can come up with a ratio of bases to genes and use that to predict what number of genes other organisms should possess. Lets try for a yeast cell. A single celled organisms that simply ferments glucose to alcohol.

Based on our obtained ratio we expect the yeast cell to have around 140 genes. But what do they have?

5,800.

So there you have it. Our ratio doesn’t stand true for other organisms. This is what we call the C-value paradox. It is the principal that the complexity of an organism does not correlate with the size of its genome.

So the study of genomics has been flourishing ever since the human genome project began. It’s a way for individuals to put their genetic studies into context to collaborate with each other and see the bigger scale and the full picture. Other projects such as the currently ongoing 100,000 genome project are the next big thing for us in genomics. They are aiming to map the genomes of tumours to see how they differ from the individuals own genome and they are also mapping rare disease genomes. Rather paradoxical to say but rare diseases are actually very common nowadays. Many millions of people have a rare disease, but they may be the only person in the world with their particular rare disease.

Genomics is paving the way for a branch of genomic medicine. In the future (the not too distant future in my opinion) we will be seeing genomic mapping of patients. This will allow clinicians to assign drug therapies to patients based on what their genomic profile says they will best respond to. Hopefully this forward movement of medicine will bring with it higher survival rates for a number of conditions. In reality as I stated in the beginning, the understanding of our genome is paramount to a successful future both clinically and scientifically. The benefits from this field are enormous already and there will be many more to come. I’ve even decided to undertake my research project in this area but there will be more to come on that in future posts. For now, I hope you’ve enjoyed reading a little bit about a flourishing field of science and learnt a little about the dangers of journalism. Perhaps your new knowledge will allow you to rest a little easier.